From disorganized data to emergent dynamic models: Questionnaires to partial differential equations

D.W. Sroczynski, F.P. Kemeth, A.S. Georgiou, R.R. Coifman, and I.G. Kevrekidis, PNAS Nexus 4 (2025).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf018

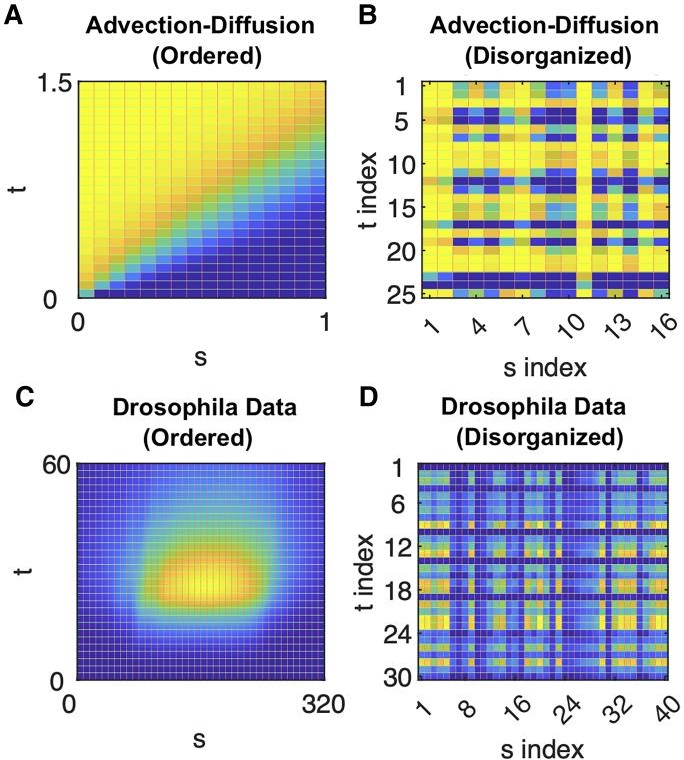

Starting with sets of disorganized observations of spatially varying and temporally evolving systems, obtained at different (also disorganized) sets of parameters, we demonstrate the data-driven derivation of parameter dependent, evolutionary partial differential equation (PDE) models capable of generating the data. This tensor type of data is reminiscent of shuffled (multidimensional) puzzle tiles. The independent variables for the evolution equations (their “space” and “time”) as well as their effective parameters are all emergent, i.e. determined in a data-driven way from our disorganized observations of behavior in them. We use a diffusion map based questionnaire approach to build a smooth parametrization of our emergent space/time/parameter space for the data. This approach iteratively processes the data by successively observing them on the “space,” the “time” and the “parameter” axes of a tensor. Once the data become organized, we use machine learning (here, neural networks) to approximate the operators governing the evolution equations in this emergent space. Our illustrative examples are based (i) on a simple advection–diffusion model; (ii) on a previously developed vertex-plus-signaling model of Drosophila embryonic development; and (iii) on two complex dynamic network models (one neuronal and one coupled oscillator model) for which no obvious smooth embedding geometry is known a priori. This allows us to discuss features of the process like symmetry breaking, translational invariance, and autonomousness of the emergent PDE model, as well as its interpretability.

On learning what to learn: Heterogeneous observations of dynamics and

establishing possibly causal relations among them

D.W. Sroczynski, F. Dietrich, E.D. Koronaki, R. Talmon, R.R. Coifman, E. Bollt, and I. G. Kevrekidis, PNAS Nexus 3 (2024).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae494

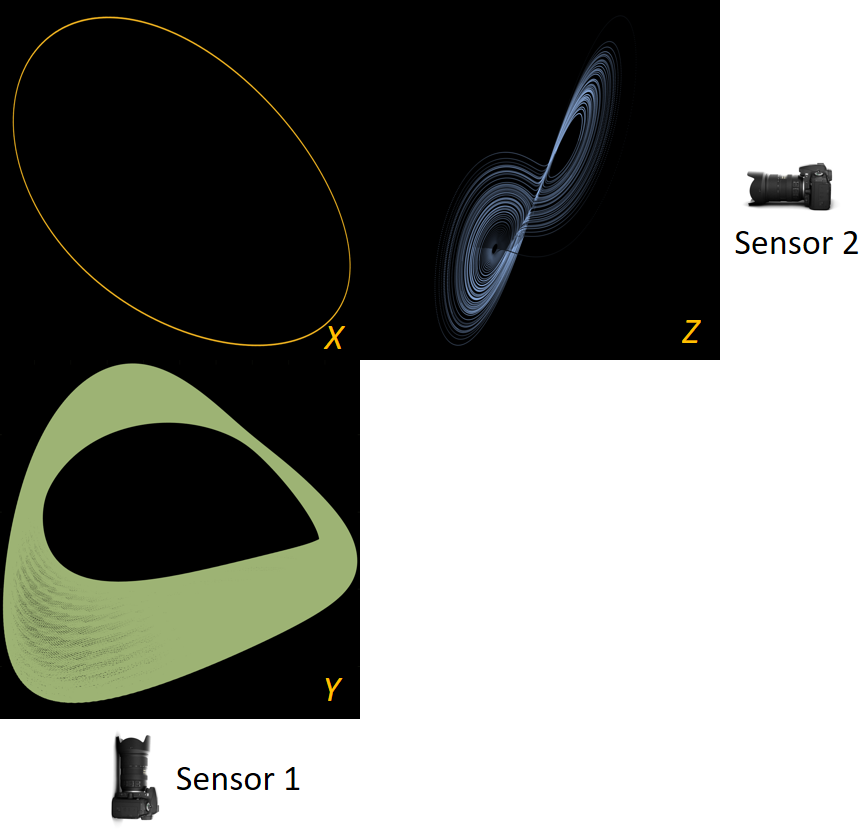

Before we attempt to (approximately) learn a function between two sets of observables of a physical process, we must first decide what the inputs and outputs of the desired function are going to be. Here we demonstrate two distinct, data-driven ways of first deciding “the right quantities” to relate through such a function, and then proceeding to learn it. This is accomplished by first processing simultaneous heterogeneous data streams (ensembles of time series) from observations of a physical system: records of multiple observation processes of the system. We determine (i) what subsets of observables are common between the observation processes (and therefore observable from each other, relatable through a function); and (ii) what information is unrelated to these common observables, therefore particular to each observation process, and not contributing to the desired function. Any data-driven technique can subsequently be used to learn the input–output relation—from k-nearest neighbors and Geometric Harmonics to Gaussian Processes and Neural Networks. Two particular “twists” of the approach are discussed. The first has to do with the identifiability of particular quantities of interest from the measurements. We now construct mappings from a single set of observations from one process to entire level sets of measurements of the second process, consistent with this single set. The second attempts to relate our framework to a form of causality: if one of the observation processes measures “now,” while the second observation process measures “in the future,” the function to be learned among what is common across observation processes constitutes a dynamical model for the system evolution.

Data‐driven Evolution Equation Reconstruction for Parameter‐Dependent Nonlinear Dynamical Systems

D.W. Sroczynski, O. Yair, R. Talmon, and I.G. Kevrekidis, Israel Journal of Chemistry 58 (2018).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ijch.201700147

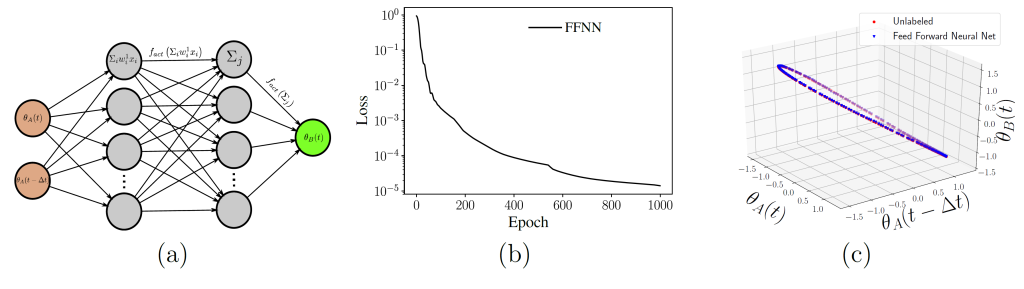

When studying observations of chemical reaction dynamics, closed form equations based on a putative mechanism may not be available. Yet when sufficient data from experimental observations can be obtained, even without knowing what exactly the physical meaning of the parameter settings or recorded variables are, data-driven methods can be used to construct minimal (and in a sense, robust) realizations of the system. The approach attempts, in a sense, to circumvent physical understanding, by building intrinsic “information geometries” of the observed data, and thus enabling prediction without physical/chemical knowledge. Here we use such an approach to obtain evolution equations for a data-driven realization of the original system – in effect, allowing prediction based on the informed interrogation of the agnostically organized observation database. We illustrate the approach on observations of (a) the normal form for the cusp singularity, (b) a cusp singularity for the nonisothermal CSTR, and (c) a random invertible transformation of the nonisothermal CSTR, showing that one can predict even when the observables are not “simply explainable” physical quantities. We discuss current limitations and possible extensions of the procedure.

Ph.D. Dissertation:

Modifying Manifold Learning Algorithms to Collect and Exploit Data for Chemical Engineering Modeling

Large data sets from observations of complex dynamical systems have become increasingly prevalent in science and engineering. The high-dimensionality of these data sets complicates (or even renders impractical) human understanding as well as many algorithmic tasks. However, many systems exhibit an effective low-dimensionality in their parameter or state space; this can enable valuable analysis/modeling tools. While analytical techniques are sometimes applicable, data-driven techniques are often required.

This dissertation makes extensive use of diffusion maps, a manifold learning algorithm which can characterize nonlinear structure in high-dimensional data. The data sets analyzed were collected under particular data collection modes relevant to chemical/biological system dynamics, motivating modifications to (extensions of) standard diffusion maps.

First, we analyze dynamical system data in the form of 3D tensors, with the axes of the tensor representing parameters, measurement channels, and time. With such data, the questionnaire metric for diffusion maps allows separate embeddings for each axis, iteratively updated based on the embeddings of the other two axes. With no a priori knowledge of the effective dimensionality of the parameter or state space, we can still learn an effective low-dimensional description (and effective evolution equations) in a data-derived emergent space. This dissertation demonstrates the approach on (a) a system described by ordinary differential equations, with the goal of bifurcation analysis, as well as on (b) a Drosophila embryonic development model that can be approximated by partial differential equations. Finally, we consider data from two different sensors, each observing different views of the same system (each sensor also having its own independent, sensor specific information).

Alternating Diffusion Maps can filter out the sensor-specific (“uncommon”) information, and construct an embedding that captures only the “common” information. With this tool (as well as its “jointly smooth functions” alternative) we can learn which variables from one sensor can be written as a function of which variables of the other sensor. We also discuss the subsequent parameterization of each sensor’s uncommon information, as well as how time delays between the two sensors’ measurements can enable the approximation of evolution equations.